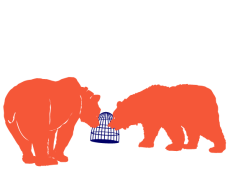

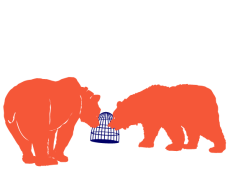

“Kosovo doesn’t have a zoo but has a bear sanctuary,” says Arif. We agree this is as well. A young state has the advantage of not having yet adopted all supposedly self-evident characteristics of our speciesism and has the luxury of questioning and reframing them.

The stray dogs in the city are all microchipped but are not accustomed to human affection.

A city bus takes me past a butcher’s shopwindow displaying skinned beef carcasses. A pretty common sight if it were not for the cute life-sized sculptures of cows and calves in front of the shop window and entrance. Children climb on them while their parents shop.

Flags, flags are hanging everywhere. Not Kosovar flags, but Albanian ones. Dual citizenship is common around here, as the Albanian one gives citizens greater freedom of movement. Prime minister Albin Kurti too holds dual citizenship. During a lecture for students of the Academy I show a deformed image of the flag’s two-headed eagle, with one eagle biting into the other’s neck. I created this image some years ago as a commentary on blood feuds among kin. After the lecture students ask me about the meaning of the image.

I leave the Academy confused. The female students have posed no questions although the majority of the images were commentaries on feminism.

Qendra Multimedia, the cultural organisation that is hosting me, is holding an international theatre festival. I go to see a handful of Kosovar plays with surtitles. I enjoy myself much more than at shows in Ljubljana; there seems to be more authenticity, more humour. The head of the organisation is also a theatre director and often collaborates with artists from Belgrade. It turns out that international funding from abroad encourages regional cooperation between politically hostile regions and fosters cultural networking. The most intelligent cooperate.

Yet, these sort of collaborations are shooting stars in a dark night.

I arrived to Pristina on Saturday and impatiently waited for Monday to comb through its bookstores. I knew very little about Kosovo. But that is why we have books. I bought a voluminous historical overview of the development of the land but that did not suffice. To understand I need poetry. I bought two collections of poems; by Agim Vinca and Lena Ibishi. The first one I will read in Bosnian, the second one in English. Reading brings me closer to Kosovo, makes it my land. In the past, this has mostly meant solidarity with workers, as it used to be lived in our former united Yugoslavia.

Now, the relentless and daring voice of 17-year-old Lena Ibishi washes over me with new, unrelenting energy. I am not sure if I am surprised or in awe. It is good.

Both ends of the street where I usually stop for my morning coffee are framed with statues of the same man. Ibrahim Rugova. A pacifist, a writer, a president. A fighter for independence. I remember seeing him on the screen of our black and white TV. I remember the scarf that wrapped itself around his neck and lent him an air of French intellectualism. Even then I was certain that the scarf could be only red, despite the monochrome images on the telly.

To get to the street I go up a hill leading past his excessively large mausoleum. But greater than the aura of the late pacifist Rugova, is the pull of the murals of the war heroes, the uniformed independence fighters, that loom over the city.

Public spaces in Pristina are often encroached upon by private property. The green surfaces hold what has been discarded and used up by former owners – trash, packaging emptied of its content. Trash, trash everywhere, also in a new, upper class neighbourhood like mine.

The other kind of private property takes up the concrete surfaces. Empty cars are safely parked all over the city’s sidewalks, and the people, they have to walk around them, down busy roads.

There is Alban Muja’s exhibition at the National Gallery, titled Whatever Happens, We Will Be Prepared about the 1999 war. A big part of the visual analysis deals with identity. The story of a Brazilian woman of Jewish heritage and with a Muslim name resonates with me most. She explains her situation as follows: “My parents were anti-Zionist Jews, hippies with high expectations.” Cheers to them, I think to myself.

A gallery, yet again, offers me refuge, a place for meditation. It does not offer answers but points towards what is crucial.

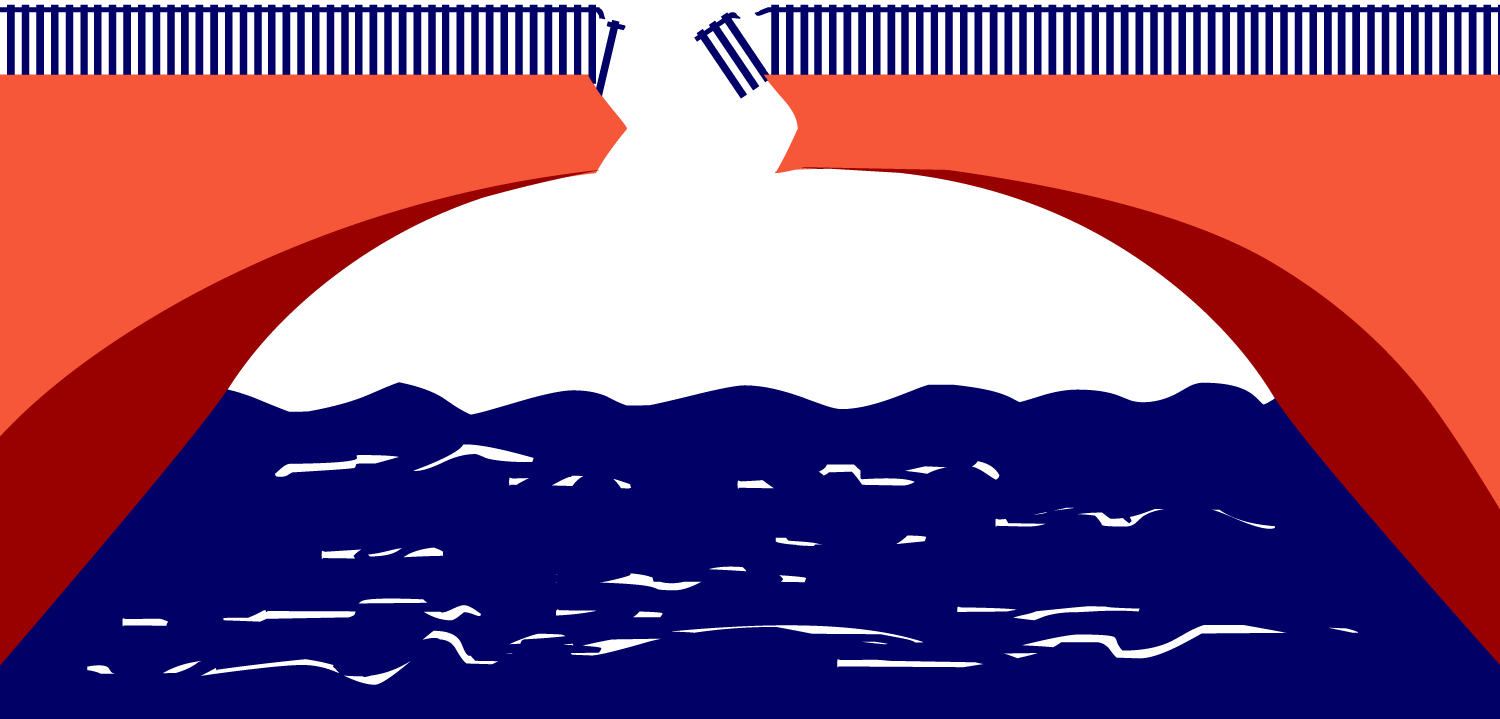

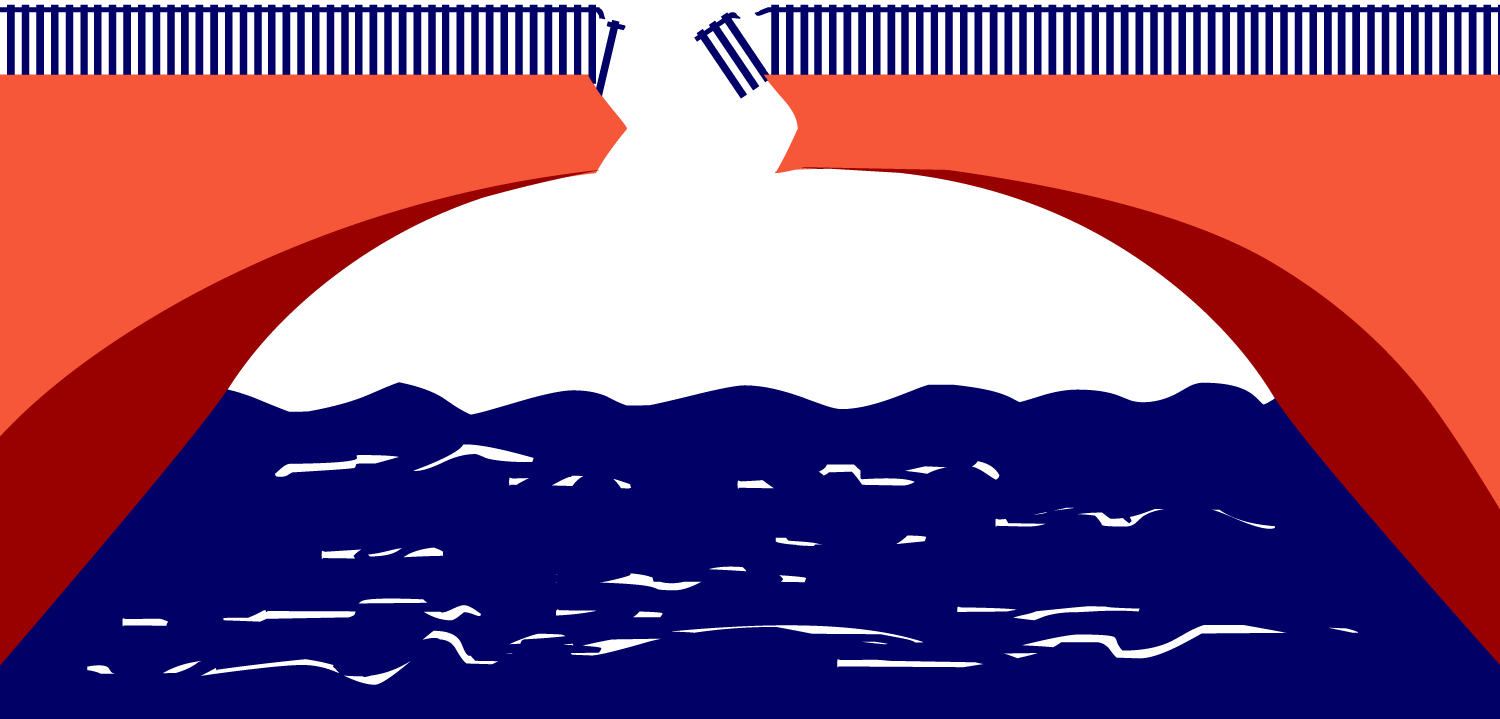

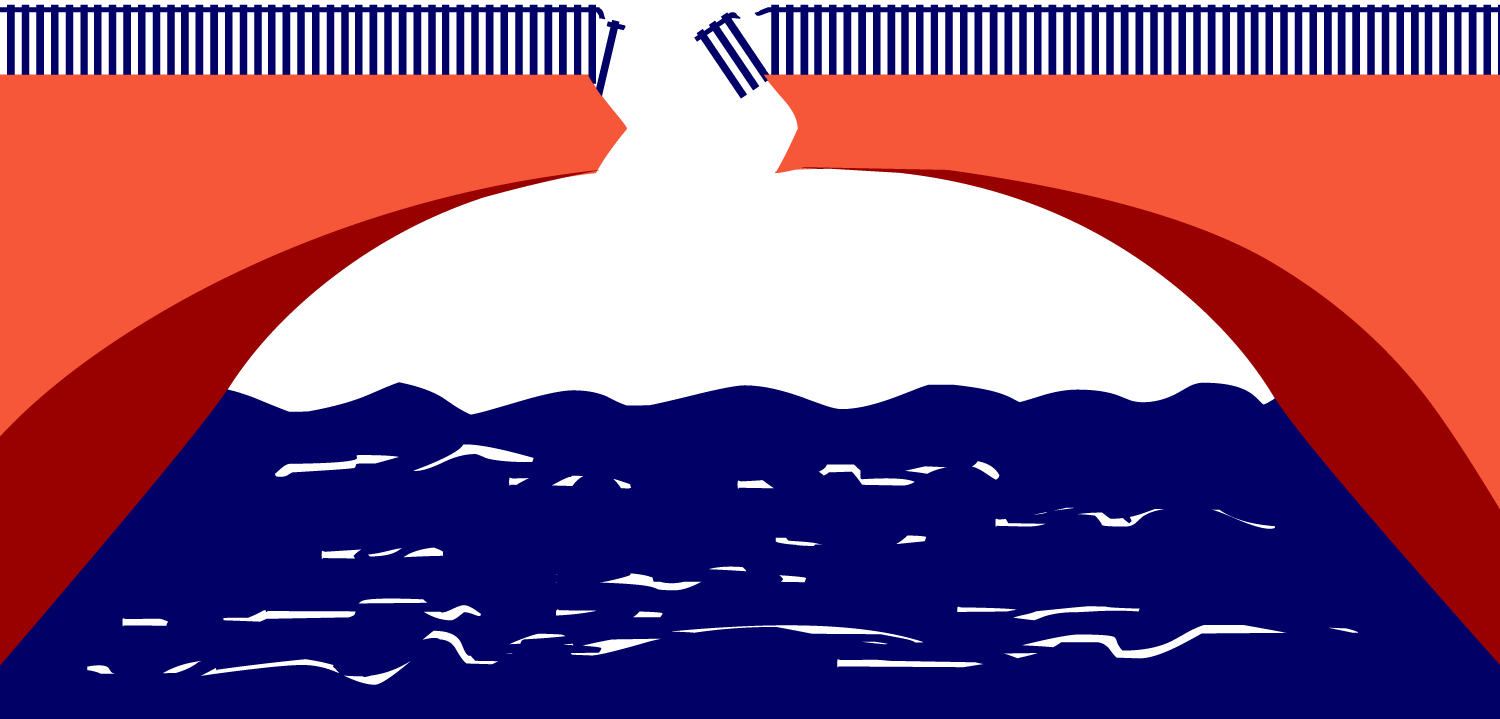

A month is too long not to move around a bit. Having gained experience with Tirana’s transport system I can now navigate the vans that are a common substitute for under-developed public transport systems. I take one of these vans to go to Mitrovica. Crossing the bridge in the city brings me to the side where the Serbs are living; something that cannot be overlooked. I feel as if I had never before in my life so clearly stepped across a border into a completely different world. And no, it is not good. We do not build bridges to stay on opposite shores.

I am somewhat comforted by the visit to Prizren, where different languages echo through the café garden and no eyebrows are raised.

Mmm, somun. I know this word. This delicious smell. It smells like the bread I ate in Bosnia as a child. The restaurant, which tries to conjure up an atmosphere of tradition and abundance, bakes the best bread in the world. I dip it into baked cream with peppers. I bite into it and purr. Its rounded belly-shape reminds me of the roof of the Kosovo National Library across the city. Architecturally it is by far the most fun building in the city.

Bread and a library. A city that has both can be the happiest place on Earth.

21st October 2021

I cannot read him in Albanian

but I understand him in Bosnian

as if he were writing in Slovenian.

Agim Vinca.

24th October 2021

sprevodnik rambo videza

je na liniji Prizren Priština

ravnokar vsem potnikom

razdelil čokobananice.

#kosovomojadežela

No one wears sunglasses.

Those speaking English most often use the phrases human rights and people from independent media.

No one hydrates oneself while walking.

1st November 2021

No need to act smart

after having spent only a day there.

But the clock next to the bridge that divides truly stands still.

There is a time of war and a time of peace.

And the time in Kosovska Mitrovica.

31st October 2021

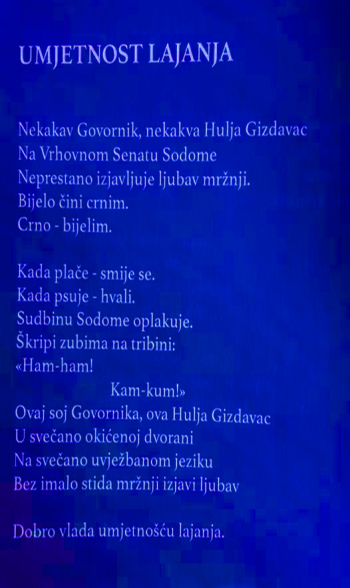

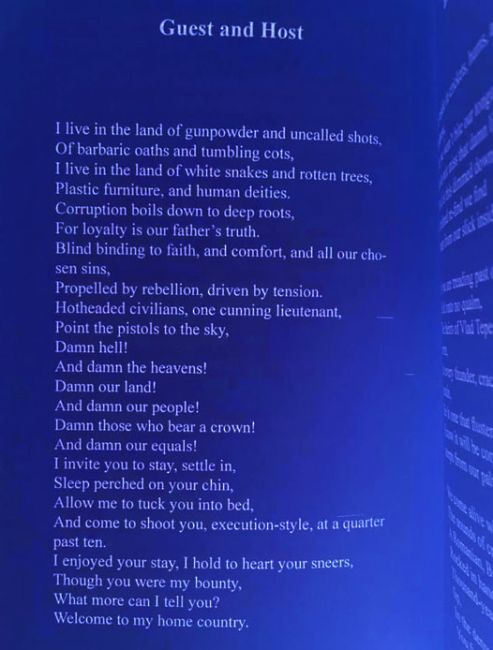

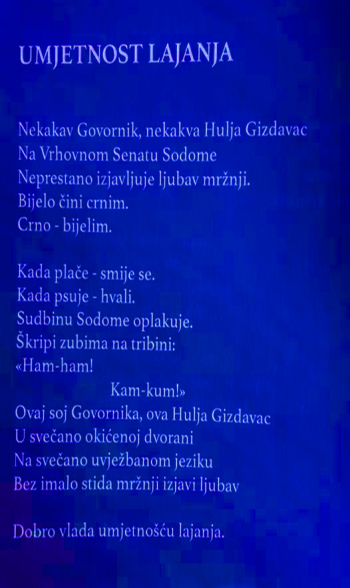

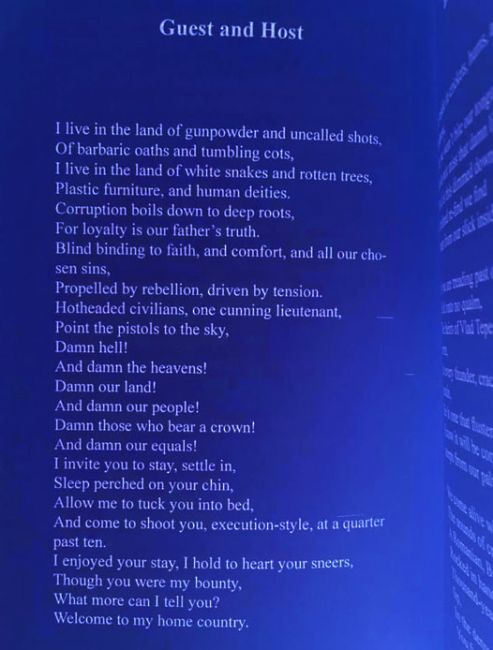

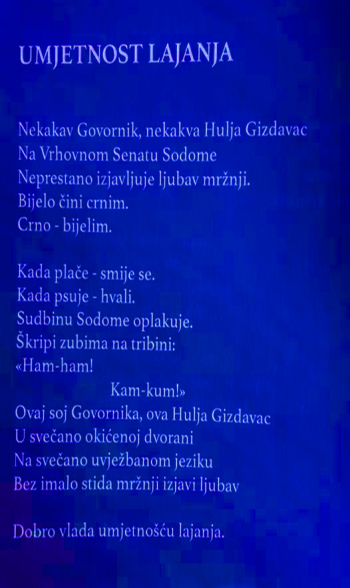

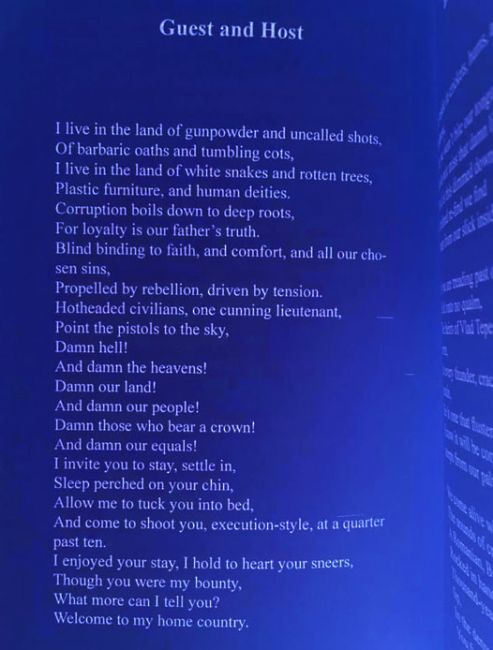

Lena Ibishi lives in Kosovo

and is 17. This is one of her poems,

dedicated to the Balkans.

The waiters in the cafés are all men.

Translated by Kristina Božič

Samira Kentrić (1976) is an artist who translates the social reality of her time into images. She enjoys creating surreal situations to highlight what she believes is most real. She works in various techniques, as many as she finds appropriate. Her main interest lies in the area where public and political expression meet with the intimate aspects of people’s everyday life. She has published three graphic novels: Balkanalije (autobiography) in 2015, Pismo Adni (a visual and literary commentary about the refugee situation) in 2016 and Adna in 2020.

Project Manager: Barbara Anderlič

Design: Beri (concept Samira Kentrić)

“Kosovo doesn’t have a zoo but has a bear sanctuary,” says Arif. We agree this is as well. A young state has the advantage of not having yet adopted all supposedly self-evident characteristics of our speciesism and has the luxury of questioning and reframing them.

The stray dogs in the city are all microchipped but are not accustomed to human affection.

A city bus takes me past a butcher’s shopwindow displaying skinned beef carcasses. A pretty common sight if it were not for the cute life-sized sculptures of cows and calves in front of the shop window and entrance. Children climb on them while their parents shop.

Flags, flags are hanging everywhere. Not Kosovar flags, but Albanian ones. Dual citizenship is common around here, as the Albanian one gives citizens greater freedom of movement. Prime minister Albin Kurti too holds dual citizenship. During a lecture for students of the Academy I show a deformed image of the flag’s two-headed eagle, with one eagle biting into the other’s neck. I created this image some years ago as a commentary on blood feuds among kin. After the lecture students ask me about the meaning of the image.

I leave the Academy confused. The female students have posed no questions although the majority of the images were commentaries on feminism.

21st October 2021

I cannot read him in Albanian

but I understand him in Bosnian

as if he were writing in Slovenian.

Agim Vinca

24th October 2021

The conductor on the Prizren-Pristina route looks like Rambo,

and is handing out choco-banana candies

to all passengers.

#kosovomojadežela #kosovomyland

Qendra Multimedia, the cultural organisation that is hosting me, is holding an international theatre festival. I go to see a handful of Kosovar plays with surtitles. I enjoy myself much more than at shows in Ljubljana; there seems to be more authenticity, more humour. The head of the organisation is also a theatre director and often collaborates with artists from Belgrade. It turns out that international funding from abroad encourages regional cooperation between politically hostile regions and fosters cultural networking. The most intelligent cooperate.

Yet, these sort of collaborations are shooting stars in a dark night.

No one wears sunglasses.

Those speaking English

most often use the phrases

human rights and

people from independent media.

I arrived to Pristina on Saturday and impatiently waited for Monday to comb through its bookstores. I knew very little about Kosovo. But that is why we have books. I bought a voluminous historical overview of the development of the land but that did not suffice. To understand I need poetry. I bought two collections of poems; by Agim Vinca and Lena Ibishi. The first one I will read in Bosnian, the second one in English. Reading brings me closer to Kosovo, makes it my land. In the past, this has mostly meant solidarity with workers, as it used to be lived in our former united Yugoslavia.

Now, the relentless and daring voice of 17-year-old Lena Ibishi washes over me with new, unrelenting energy. I am not sure if I am surprised or in awe. It is good.

No one hydrates oneself while walking.

Both ends of the street where I usually stop for my morning coffee are framed with statues of the same man. Ibrahim Rugova. A pacifist, a writer, a president. A fighter for independence. I remember seeing him on the screen of our black and white TV. I remember the scarf that wrapped itself around his neck and lent him an air of French intellectualism. Even then I was certain that the scarf could be only red, despite the monochrome images on the telly.

To get to the street I go up a hill leading past his excessively large mausoleum. But greater than the aura of the late pacifist Rugova, is the pull of the murals of the war heroes, the uniformed independence fighters, that loom over the city.

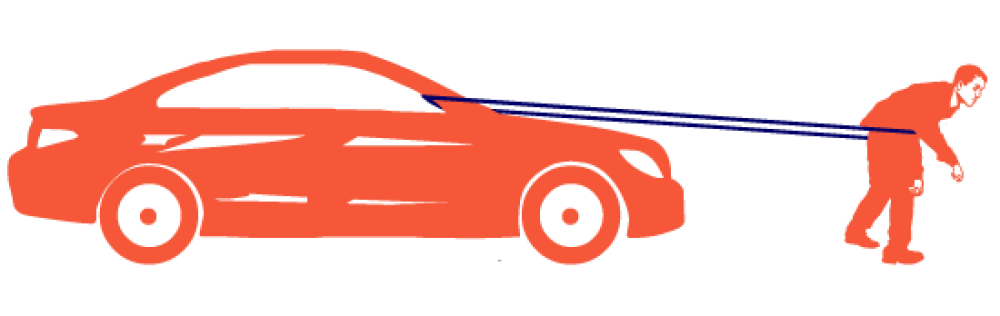

Public spaces in Pristina are often encroached upon by private property. The green surfaces hold what has been discarded and used up by former owners – trash, packaging emptied of its content. Trash, trash everywhere, also in a new, upper class neighbourhood like mine.

The other kind of private property takes up the concrete surfaces. Empty cars are safely parked all over the city’s sidewalks, and the people, they have to walk around them, down busy roads.

1st November 2021

No need to act smart

after having spent only a day there.

But the clock next to the bridge that divides truly stands still.

There is a time of war and a time of peace.

And the time in Kosovska Mitrovica.

There is Alban Muja’s exhibition at the National Gallery, titled Whatever Happens, We Will Be Prepared about the 1999 war. A big part of the visual analysis deals with identity. The story of a Brazilian woman of Jewish heritage and with a Muslim name resonates with me most. She explains her situation as follows: “My parents were anti-Zionist Jews, hippies with high expectations.” Cheers to them, I think to myself.

A gallery, yet again, offers me refuge, a place for meditation. It does not offer answers but points towards what is crucial.

A month is too long not to move around a bit. Having gained experience with Tirana’s transport system I can now navigate the vans that are a common substitute for under-developed public transport systems. I take one of these vans to go to Mitrovica. Crossing the bridge in the city brings me to the side where the Serbs are living; something that cannot be overlooked. I feel as if I had never before in my life so clearly stepped across a border into a completely different world. And no, it is not good. We do not build bridges to stay on opposite shores.

I am somewhat comforted by the visit to Prizren, where different languages echo through the café garden and no eyebrows are raised.

31st October 2021

Lena Ibishi lives in Kosovo

and is 17. This is one of her poems,

dedicated to the Balkans.

Mmm, somun. I know this word. This delicious smell. It smells like the bread I ate in Bosnia as a child. The restaurant, which tries to conjure up an atmosphere of tradition and abundance, bakes the best bread in the world. I dip it into baked cream with peppers. I bite into it and purr. Its rounded belly-shape reminds me of the roof of the Kosovo National Library across the city. Architecturally it is by far the most fun building in the city.

Bread and a library. A city that has both can be the happiest place on Earth.

The waiters in the cafés are all men.

Translated by Kristina Božič

Samira Kentrić (1976) is an artist who translates the social reality of her time into images. She enjoys creating surreal situations to highlight what she believes is most real. She works in various techniques, as many as she finds appropriate. Her main interest lies in the area where public and political expression meet with the intimate aspects of people’s everyday life. She has published three graphic novels: Balkanalije (autobiography) in 2015, Pismo Adni (a visual and literary commentary about the refugee situation) in 2016 and Adna in 2020.

Project Manager: Barbara Anderlič

Design: Beri (concept Samira Kentrić)

“Kosovo doesn’t have a zoo but has a bear sanctuary,” says Arif. We agree this is as well. A young state has the advantage of not having yet adopted all supposedly self-evident characteristics of our speciesism and has the luxury of questioning and reframing them.

The stray dogs in the city are all microchipped but are not accustomed to human affection.

A city bus takes me past a butcher’s shopwindow displaying skinned beef carcasses. A pretty common sight if it were not for the cute life-sized sculptures of cows and calves in front of the shop window and entrance. Children climb on them while their parents shop.

Flags, flags are hanging everywhere. Not Kosovar flags, but Albanian ones. Dual citizenship is common around here, as the Albanian one gives citizens greater freedom of movement. Prime minister Albin Kurti too holds dual citizenship. During a lecture for students of the Academy I show a deformed image of the flag’s two-headed eagle, with one eagle biting into the other’s neck. I created this image some years ago as a commentary on blood feuds among kin. After the lecture students ask me about the meaning of the image.

I leave the Academy confused. The female students have posed no questions although the majority of the images were commentaries on feminism.

21st October 2021

I cannot read him in Albanian

but I understand him in Bosnian

as if he were writing in Slovenian.

Agim Vinca.

24th October 2021

The conductor on the Prizren-Pristina route looks like Rambo,

and is handing out choco-banana candies

to all passengers.

#kosovomojadežela #kosovomyland

Qendra Multimedia, the cultural organisation that is hosting me, is holding an international theatre festival. I go to see a handful of Kosovar plays with surtitles. I enjoy myself much more than at shows in Ljubljana; there seems to be more authenticity, more humour. The head of the organisation is also a theatre director and often collaborates with artists from Belgrade. It turns out that international funding from abroad encourages regional cooperation between politically hostile regions and fosters cultural networking. The most intelligent cooperate.

Yet, these sort of collaborations are shooting stars in a dark night.

No one wears sunglasses.

Those speaking English most often use the phrases human rights and people from independent media.

I arrived to Pristina on Saturday and impatiently waited for Monday to comb through its bookstores. I knew very little about Kosovo. But that is why we have books. I bought a voluminous historical overview of the development of the land but that did not suffice. To understand I need poetry. I bought two collections of poems; by Agim Vinca and Lena Ibishi. The first one I will read in Bosnian, the second one in English. Reading brings me closer to Kosovo, makes it my land. In the past, this has mostly meant solidarity with workers, as it used to be lived in our former united Yugoslavia.

Now, the relentless and daring voice of 17-year-old Lena Ibishi washes over me with new, unrelenting energy. I am not sure if I am surprised or in awe. It is good.

No one hydrates oneself while walking.

Both ends of the street where I usually stop for my morning coffee are framed with statues of the same man. Ibrahim Rugova. A pacifist, a writer, a president. A fighter for independence. I remember seeing him on the screen of our black and white TV. I remember the scarf that wrapped itself around his neck and lent him an air of French intellectualism. Even then I was certain that the scarf could be only red, despite the monochrome images on the telly.

To get to the street I go up a hill leading past his excessively large mausoleum. But greater than the aura of the late pacifist Rugova, is the pull of the murals of the war heroes, the uniformed independence fighters, that loom over the city.

Public spaces in Pristina are often encroached upon by private property. The green surfaces hold what has been discarded and used up by former owners – trash, packaging emptied of its content. Trash, trash everywhere, also in a new, upper class neighbourhood like mine.

The other kind of private property takes up the concrete surfaces. Empty cars are safely parked all over the city’s sidewalks, and the people, they have to walk around them, down busy roads.

1st November 2021

No need to act smart

after having spent only a day there.

But the clock next to the bridge that divides truly stands still.

There is a time of war and a time of peace.

And the time in Kosovska Mitrovica.

There is Alban Muja’s exhibition at the National Gallery, titled Whatever Happens, We Will Be Prepared about the 1999 war. A big part of the visual analysis deals with identity. The story of a Brazilian woman of Jewish heritage and with a Muslim name resonates with me most. She explains her situation as follows: “My parents were anti-Zionist Jews, hippies with high expectations.” Cheers to them, I think to myself.

A gallery, yet again, offers me refuge, a place for meditation. It does not offer answers but points towards what is crucial.

A month is too long not to move around a bit. Having gained experience with Tirana’s transport system I can now navigate the vans that are a common substitute for under-developed public transport systems. I take one of these vans to go to Mitrovica. Crossing the bridge in the city brings me to the side where the Serbs are living; something that cannot be overlooked. I feel as if I had never before in my life so clearly stepped across a border into a completely different world. And no, it is not good. We do not build bridges to stay on opposite shores.

I am somewhat comforted by the visit to Prizren, where different languages echo through the café garden and no eyebrows are raised.

31st October 2021

Lena Ibishi lives in Kosovo

and is 17. This is one of her poems,

dedicated to the Balkans.

Mmm, somun. I know this word. This delicious smell. It smells like the bread I ate in Bosnia as a child. The restaurant, which tries to conjure up an atmosphere of tradition and abundance, bakes the best bread in the world. I dip it into baked cream with peppers. I bite into it and purr. Its rounded belly-shape reminds me of the roof of the Kosovo National Library across the city. Architecturally it is by far the most fun building in the city.

Bread and a library. A city that has both can be the happiest place on Earth.

The waiters in the cafés are all men.

Translated by Kristina Božič

Samira Kentrić (1976) is an artist who translates the social reality of her time into images. She enjoys creating surreal situations to highlight what she believes is most real. She works in various techniques, as many as she finds appropriate. Her main interest lies in the area where public and political expression meet with the intimate aspects of people’s everyday life. She has published three graphic novels: Balkanalije (autobiography) in 2015, Pismo Adni (a visual and literary commentary about the refugee situation) in 2016 and Adna in 2020.

Project Manager: Barbara Anderlič

Design: Beri (concept Samira Kentrić)